Wall plotter update #7: semester in review, major problems, solutions and important lessons

As the semester comes to a close, I have to evaluate the status of my projects and decide whether or not I want to continue pursuing them. My intention was to create a wall plotter this semester to explore alternative media for art, as well as to excite students and faculty about the new possibilities. In addition, I wanted to use this project as a way to gain some experience in fabrication and shop skills as I fabricate parts.

Semester in review

When I began this project, I knew that the most difficult part would be in the physical fabrication and assembly of the parts, but I had no way of knowing just how difficult it would be. In fact, I distinctly remember telling people that this project “should only be a weekend project”! A weekend project for someone who has access to a 3D printer, a CNC machine and a couple hundred dollars of funding, that is.

At the beginning of this semester, I already had a good idea of the essential hardware components needed to make the system run: a couple of motors, motor drivers, a power supply and a microcontroller. Luckily, the professor I am working with was able to get a small amount of money from his department (~$100) to help with this, so I was able to acquire the parts by February 3rd. From there, it was a trivial matter to wire everything up and run some tests by February 7th. Unfortunately, this is when the problems began.

Lack of funding

After purchasing the electronics, all funding dried up. The professor I am working with doesn’t think he’ll be able to acquire any amount of funding until at least July 1st, and maybe not even then. Not a great thing to hear when the semester ends on May 3rd, and things need to be purchased several months before that date. As a graduate student at UNK, I have no discretionary funding – my meager stipend is only enough to pay for housing and food, and not much else. I searched high and low in both my college (College of Education) and with the University, and found that no funding was available for my project. Rather than letting this get me down, I decided to try to fabricate everything by hand! As you might imagine, this was a whole new world of difficulty!

Lack of resources

By February 14th, I knew that I needed to fabricate a set of pulleys to attach to my motors. With a CNC machine, laser cutter or 3D printer, this would be trivial; just draw the shapes in a vector drawing program and send the files to the machine (via a CAM program). The problem is, I have no access to any of these kinds of machines, and local machine shops were advising me not to utilize them (due to high costs of running their machines). In fact, the vast majority of the difficulty in this project this semester did not have anything to do with the project itself, but in gaining access to machinery and fabricating parts for this project. It took over two months to find any place willing to help me or allow me access to machinery! If you’d like to learn more about this, I’ll outline it all in the next section.

Calendar of events for this semester

Here is how my progress looked this semester, in calendar form:

Securing the proper resources, in depth

In this section, I’ll discuss the entire process of my attempts to secure the proper resources in my area. By “proper resources”, I mean machinery capable of producing the parts I need for the wall plotter, whether it be CNC machinery, laser cutters, 3D printers or just basic shop tools like a drill press and table saw. Keep in mind that this process took about two months and is still on-going! It is not essential that you read this section, but if you want to understand the processing of “making” in a small town like Kearney, Nebraska, this could provide some helpful insight for you.

- UNK’s Physics Department: as an undergraduate, I had a minor in Physics and spent some time getting to know the faculty a little bit, and I knew that two of the faculty members had experience in fabrication and might be able to teach me basic shop skills. I learned that there was actually a basic machine shop in the basement of Bruner Hall (our science building) which is home to a small lathe and other machines. I thought this would be a perfect opportunity to learn how to fabricate things! I contacted the Chair of Physics, and asked if he could help me fabricate two pulleys. I sent him the following message on February 28th:

Dr. Trantham,

This semester I’m working on a couple of projects that I need to fabricate parts for. Trouble is, I need to be fairly precise, and don’t think I can do it myself (yet). No one I’ve contacted so far on campus have been willing to help me fabricate or learn how to fabricate the parts I need, so I was hoping you could help me out.

Would be able to meet up for a little while and take a look at my plans and ideas? I’ve got CAD drawings, sketches, BOMs and basic plans, I just need some advice/help making them real.

– Jason WebbThat night, he responded with:

“depending on what the part is , you will need access to a lathe and/or a mill. i do not have either. local machine shops will make stuff, but you will pay $ per hour”

– Dr. Ken Trantham, Feb 23rdLater that week, I paid a visit to the Physics office to try to get some more advice, and found that he was out of the office. I walked downstairs and went to the machine shop, only to find the door locked and the lathe inside running. I am still not quite sure why he said that he doesn’t have a lathe, but I decided to continue exploring options rather than stress any personal relationships.

- UNK’s Industrial Technology Department: The next logical stop for me was UNK’s Industrial Technology Department, home to a workshop stocked with basic shop machinery and possibly a wood lathe or mill. I paid a visit to Dr. Kennard Larson and explained my goals and intentions to him. In person, he responded with enthusiasm and seemed very happy to help, but he said he needed to get permission from the Chair of the College of Business and Technology before I could do anything. In order to help, I mentioned that a veteran machinist in the Physics department (Dr. Robert Price) was interested in sponsoring me and mentoring me in the operation of any machines, so that the lab director didn’t have to take time out of his day to watch me. Within a week, I received the following e-mail from the Chair:

Jason,

I’ve been informed by Dr. Larson that you’ve requested usage of the construction lab and the equipment located in the lab. Each of the labs in the ITEC Department are managed by specific faculty members and each lab has specific safety requirements which are not optional.

Unfortunately Dr. Larson does not have the time or capacity to work with you at this time to provide access to this lab. Since he is the faculty member responsible for this lab I will respect his decision. It really isn’t an option to allow you to be “sponsored” by another faculty member since the lab and associated safety protocols are under the overview of Dr. Larson.

Tim Obermier, Ph.D. Chair and Professor

Department of Industrial TechnologyTo which I responded:

I understand. I am not looking to circumvent any safety protocols, so if this prevents me access for the lab, that’s reasonable to me.

I can understand if Dr. Larson is too busy with existing curricular activities to keep an eye on me, so I will work with him to find out when he might be able to find time in the future and how we might be able to work together.

Do you have any advice for students like myself who may not be direct students in the ITEC department or CBT college, but still want to gain experience and knowledge in machining and workshop skills? Part of my graduate work requires me to gain learn about either manual machining / fabrication methods or CNC technology, but I have yet to find a way to be able to pursue this. Does ITEC offer any courses or workshops in these areas that I can look into? I’m especially interested in learning about how I can make progress to that end as soon as possible (this semester), in order to make progress on my graduate work.

I’m very interested in expanding my skillset and fabricating parts for my graduate work, and I’d obviously love to find a way to work with an entity on the UNK campus, rather than an outside machine shop. ITEC seems to have the best working labs on campus, and the resources to keep them up to date and functional, so I’d be extremely grateful to find a way to work with the department to achieve my goals.

Thanks!

Which was replied to within a day with the following:

Jason,

It is important to note the ITEC Department doesn’t have a machining lab or any CNC machines. The RP machine is only used by industry partners, we do not use it for the academic environment. I’m sorry but we do not offer special workshops for the general use of labs.

I don’t have a solution for you on the UNK campus, but you may want to consider Central Community College, they have more specific labs which should meet your objectives.

Tim Obermier, Ph.D. Chair and Professor

Department of Industrial TechnologyNote that I never mentioned a “RP” machine, nor that I think the CBT has a machine shop. I approached this department with the intent of being able to learn about and use whatever machinery they had available, such as drill presses, table saws and wood lathes. I was hoping that by exercising some basic shop skills, I can get a better practical understanding of what I’m trying to do and how hard or easy it is.

It is somewhat disheartening to hear from the largest university in the area that I needed to go to a community college 40 miles away in order to learn how to make something. To me, this response is symptomatic of a much broader problem with out society than simply one student not being allowed into a lab. I wondered if students like me are falling into this problem all across the country, and what this means for the society at large.

- Local machine shops: After exploring all of the available options on campus, I realized I wasn’t going to be able to use these resources, so I began visiting local machine shops to see if I could hit gold. Keep in mind, this was near the middle of March, and I only had one more full month left before the semester ended, so I needed to make something happen soon.

I visited Concepts Machining Company in Kearney and met with the owner, and discussed my goals and problems. He was very interested in my project and wanted to help out, but from the beginning, he advised me that any machine shop in town would charge me at least $60 an hour to create even small parts using their machines, not including materials. He estimated that it would take at least 2-3 hours of work to create what I need. Therefore, I was faced with paying at least $120 for a pair of wooden pulleys which may or may not work as I intended them to (in the end, they didn’t). He strongly advised me to buy a coping saw and create the parts by hand, rather than visiting a machine shop. Since this was the most I had to work with so far, I decided to do just that. I purchased a coping saw and spent over 10 hours manually sawing two circular discs out of MDF!

Next, I visited another, larger machine shop in town called Dyna-Tool, which boasts on their website a great deal of very powerful machinery, as well as “CAD room computers updated every 6 months to the latest technology”. I visited the machine shop and took a tour, and was very impressed with the environment, the work, the machines and the level of expertise in this shop. I asked if I could submit to them DXF files (CAD files) and provide them with materials, and ask how much it would cost. The shop owner was interested, but was very quick to tell me that it would cost at least a couple hundred dollars ($60/hr with machine setup and running times), and they couldn’t take on any clients at the time anyway, because they were already being pushed by a large company in town to create parts for them – they simply couldn’t do it if they wanted to.

- UNK’s Sculpture Department: in the middle of March, the professor I am working on this project with, Dr. Mark Hartman, learned about the difficulties I had been having to this point in fabricating my parts. At this point, it had been nearly one month since I could make any real, physical progress on my project, and I was getting quite frustrated. I mentioned that I was about to purchase a drill press, stretching my thin personal budget even thinner, just to try to make some progress on the project. He says that the Sculpture lab should have some basic shop machines, so he brings me by and introduces me to the Sculpture professor, Chad Fonfara. Although almost my entire undergraduate experience was in the same building as this lab, I had never heard of it or knew what was there. I knew that there was some glassblowing activities going on, but that was about all I knew.

From the beginning, Chad was much more enthusiastic and helpful than anyone I had encountered in the last few months. He shows me around the shop, discusses the activities that go on day-to-day and even introduces me to a couple of the machines that I needed to use. On March 19th, I came back to the lab with materials and plans in hand, and finished up my MDF pulleys using the lab’s drill press and a jigsaw.

All in all, it took approximately two months for me to create two wooden pulleys out of MDF! I attached the pulleys to my motors and begin doing some tests, and within a week, the pulleys fail! They are simply too large in diameter, which results in too much torque for the press-fit joint to accommodate, so before too long, the pulleys begin spinning around the shafts of the motors.

It’s important to note that everything else in this project is in place and ready. The electronics have been working since early February. The software has been created and customized. I even built a program that generates imagery to draw, ready to be loaded onto the finished system. But none of that is important if the mechanical system doesn’t work.

Solutions and thoughts about moving forward

The challenges this semester boil down to two main points: funding and resources. Funding was a big issue early on, and I really didn’t have a good solution until just a few weeks ago. After much discussion with various people and research on my own, I decided to take out student loans to cover my project costs. In fact, I took out over $8,000 in loans for the sole purpose of executing projects and acquiring resources!

In the above section, I discussed my efforts in acquiring the right resources, but I still feel that I’m not quite satisfied with the resources I have access to. Having access to a drill press and other basic shop machines is indeed helpful, but its not the best solution. The machines I have access to are not easily to use within tight tolerances. In other words, if I need to make a pulley that is 10″ in diameter, it would still be quite difficult to make it within 0.001″ of that size. Fabrication also needs to be easy, because the work I’m doing is experimental and bound to need iterations and changes over time. If it takes two months to fabricate a single set of pulleys, I can’t experiment with different sizes easily. Even if the pulleys take two weeks, that is still too long. Parts need to go from design to product within 2-3 days!

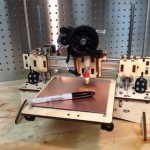

Rapid prototyping

While working on this project, I kept thinking, “What would make this process easier? What do I WISH I had?” The answer has been the same the entire semester: machines that make. In particular, a 3D printer would be incredibly useful for me, and would allow me to design and create parts in a matter of hours rather than days, weeks or months. Therefore, I will be planning to buy a 3D printer of my own within the next month or so! The most attractive printer to me right now is the Printrbot, but I do need to wait another couple weeks to find out which to buy.

While working on this project, I kept thinking, “What would make this process easier? What do I WISH I had?” The answer has been the same the entire semester: machines that make. In particular, a 3D printer would be incredibly useful for me, and would allow me to design and create parts in a matter of hours rather than days, weeks or months. Therefore, I will be planning to buy a 3D printer of my own within the next month or so! The most attractive printer to me right now is the Printrbot, but I do need to wait another couple weeks to find out which to buy.

Another machine that could be very helpful is a CNC mill/router or a laser cutter. While these can be bought on the small scale (see ShapeOko), I feel that a full-sheet sized machine would be extremely helpful. A machine like a ShopBot or a Lasersaur could take large sheets of plywood, acrylic, cardboard, foam or other materials and cut out shapes that you draw on the computer. In my opinion, this technology has enabled a huge amount of progress recently in the DIY world; in fact, the Printrbots and MakerBot Industries’ 3D printers and many more projects rely on laser cut wood to build their machines! However, these are not yet suitable for home hobbyists, so I would have to try to convince a department at UNK to purchase one.

Another machine that could be very helpful is a CNC mill/router or a laser cutter. While these can be bought on the small scale (see ShapeOko), I feel that a full-sheet sized machine would be extremely helpful. A machine like a ShopBot or a Lasersaur could take large sheets of plywood, acrylic, cardboard, foam or other materials and cut out shapes that you draw on the computer. In my opinion, this technology has enabled a huge amount of progress recently in the DIY world; in fact, the Printrbots and MakerBot Industries’ 3D printers and many more projects rely on laser cut wood to build their machines! However, these are not yet suitable for home hobbyists, so I would have to try to convince a department at UNK to purchase one.

Important lessons learned this semester

When I decided to document my experiences in building this projects in this way, it was not intended to be a passive-aggressive outlet of frustration, but rather to provide an inside view of being a budding Maker in a small town. That being said, I cannot deny that I have encountered my fair share of frustration this semester, so some of that may have seeped into this post. Luckily, since this is a personal blog, I don’t feel a strong need to edit this post for pure objectivity – I hope I’ve given an accurate picture of what my journey has been like so far, with all the ups and downs.

I have spent a great deal of time this semester trying to answer important questions for myself. Questions like, “Why did this take so long?” and “What would a ‘perfect’ execution look like?” In that respect, I feel this semester has been greatly successful and beneficial to me personally. Professionally and academically, I may not have produced as much as I wanted, or exactly what I wanted, but that is not the complete story. The following is a (probably incomplete) list of personal lessons I learned this semester, which I hope helps out other Makers out there.

- Don’t fight an impossible battle

In my area, very few people truly make things, and very few of those people are friendly towards hobbyists or curious Makers. In fact, in my experience, the Maker Movement (the idea of “hacking” at home) is completely unknown – I have personally met less than a half dozen people who have even heard of it. Rather than doing what I did and visiting shops in person and hoping for some help, try to find a way to secure what you need yourself. Purchase a cheap 3D printer ($550+) or buy some simple shop tools like a drill press and a table saw ($100 each for entry-level models). The following two pieces of wisdom have been resonating with me quite deeply recently:“Rather than raging against the machine, build a better machine!”

– Chris Hackett“You must be the change you want to see in the world.”

– Mahatma Gandhi - Don’t listen to the ‘experts’

Time and time again when I explain my project to people who ‘make’ for a living (machinists, tool and die makers, etc.), I tend to get a pretty predictable reaction: either an incredulous look or a chuckle. At first, I was personally offended by this because I thought they were laughing at me or my idea. While this may or may not be true, I have better reason to believe that the experts laugh at the naivety I express when I say I want to make something, because to them, making things is difficult and requires years of experience, and demands respect. Expert makers like machinists believe that in their line of work they need, at a minimum, machines that costs thousands and thousands of dollars. So when a student or a hobbyist comes into a shop and says, “I want to do what you do, but without the hard stuff,” they probably feel a bit offended themselves! When I say I want to build this or that out of wood, every single person said that it is completely impossible. Then I show them the Printrbot, the Makerbot Replicator or other DIY CNC machines and they say, “whatever, I know I’m right.” - Invest in tools that let you try out ideas quickly and easily

If you were to ask me today that I could have one wish granted by the magical Maker Genie, but I can only have one thing, I could give you the answer in a heartbeat. A 3D printer like the Replicator! I already own a variety of hand saws, measuring tools, clamps, and power tools (table saw, miter saw, circular saw, router, jigsaw and hand drill), but they all have very finite purposes. I can’t make pulleys, plastic adapters, enclosures or fixtures very easily with these tools. However, with a 3D printer, I could literally ‘print’ any small shape I can imagine! I could design and print pulleys in a single day, or print out 10 different kinds of pen carriages, just to see how they feel. In fact, I would so far as to say that I would trade many of the tools I own just to have a 3D printer on my workbench. Luckily, I will be buying one soon, but it would have been better to have one in January! - Don’t bite off more than you can chew

This lesson is particularly hard for me to accept personally, and doesn’t come without a lot of serious personal inquiry. There is a huge difference between knowing you are capable of doing something, and actually doing it. Sometimes, you don’t have a say in whether or not you can accomplish something, because actions are the result of will power and resources working together. Even if your will power is high, if you don’t have the correct machine, you can’t execute the work properly. For example, if you want to put a screw into a piece of wood, but don’t have a screwdriver, what do you do? Sometimes, if you’re lucky and shrewd, you can improvise. But sometimes, you simply can’t improvise, and that is a hard pill to swallow. I somehow have it in my head that with the right amount of will power, anything is possible. Perhaps reality is somewhat more complicated than that. - Iterate early, iterate often

If I had been able to produce a set of pulleys in February, I would have been able to test them out and realize that they wouldn’t work. I could learn from the problem and correct it, then produce another, small set of pulleys and test them out. However, without the resources to do so, I was stuck with having to expect the pulleys to work without having the practical evidence to confirm or deny this assumption. This is really a re-assertion of Lesson #3 above – with the right tools, one could iterate early and often and generate a dozen pulley prototypes in the same amount of time it took me to fabricate one and rapidly gain a large amount of experience and intuitive insight into the problem.

Next steps and future goals

So the big question is, since the semester ends on May 3rd, will I continue working on the wall plotter? The answer is “yes!”. I’m lucky enough to be working on a project that I am personally interested in, and that interest extends beyond academia. However, I cannot continue to work in the same fashion that I have been the last few months. The amount of stress and frustration that I’ve encountered in this seemingly simple project has been much higher than I expected, and much higher than it needs to be.

Therefore, it seems to me that at this point, the best way to make progress on this project is to stop working on it! Not permanently, obviously, but just for the next couple months as I direct all of my energy and finances towards acquiring and upgrading my personal resources to make it easier to get this kind of work done. The first step will be to purchase a 3D printer of my own, but there have been some encouraging signs of progress on campus. I have heard that the UNK Visual Communication and Design program (graphic design) will be purchasing a Makerbot Replicator soon, and are very interested in the possibility of purchasing a laser cutter. Good things are on the horizon, but its never easy to look back at several months of work and be unhappy. Hopefully I can get the right pieces in place this summer to make my fall semester go smoother!